Theme and Storyline

Trends in Animal Exhibition.

Landscape or habitat immersion design, the concept of displaying animals in the context of nature rather than in the context of architecture, has gained wide acceptance around the world.

Immersion Design

Immersion Design is a concept with a goal to immerse animals and guests in the same re-created theme area, habitat or landscape. Animals and visitors are separated by hidden barriers. In its purest sense, landscape immersion design takes the position "nature is the best model". This concept has gradually gained world-wide acceptance and is often considered the best practice.

"The landscape immersion approach arose from the naturalistic exhibit traditions of Hagenbeck and Akeley. It is responsive to our increased concern to protect wild animals and wild places by educating and involving urban populations. This approach benefited mutually from parallel development in exhibit materials technology and craft and the introduction of contextual exhibits in museums.

Use of immersion exhibits seems to give great scope to affective learning and, based on its present popularity, adds important recreational dimensions as well. “ Jon Coe "Landscape Immersion —- Origins and Concepts "

Landscape or habitat immersion gained wide acceptance before the concept was expanded to include vernacular architectural and cultural environments in zoo exhibits. This concept was first developed by Carl Hagenbeck in 1907 and was revived and expanded in the 1980's. It adds an important human dimension to immersion design tremendously increasing education opportunities and value.

"This concept has made a strong come back... in recent zoo exhibits at Zoo Atlanta, Bronx Zoo and Woodland Park Zoo. These current exhibits emphasise the interrelationship between traditional peoples and wildlife, point to a more naturalistic lifestyle alternative and, in some cases, alert visitors to the parallel extinction of wilderness and traditional cultures." - Jon Coe "The Evolution of Zoo Animal Exhibits "

Cultural Resonance

Activity-based design emphasises behavioural management as advocated by Hediger in the 1950's. This concept was updated in the 1980's to integrate the fields of behavioural enrichment, animal training, husbandry and design. Improved animal activity and fitness levels result in more active and interesting animal displays.

"Activity-based design begins with the premise that the animals' long term well-being is paramount and that environments, programs and procedures which advance this goal are frequently of great interest to the visiting public. Healthy animal with stimulating behavioral choices tend to be more active. Therefore, opportunity-rich animal environments, enlightened animal care and caretaker devotion should all be made visible to the public within a setting which demonstrates the animals' innate competence." - Jon Coe "Entertaining Zoo Visitors and Zoo Animals: An Integrated Approach"

Activity Based Design

This trend which increase affiliative behaviour and reduces aggression in social species, including people, gives a much better message about animals and their place in nature.

"'Building a bond between people and the planet', the Louisville Zoo motto, describes one of the major roles of zoos. Building upon the work of Hediger, Lorenz, Skinner and contemporary behaviourists, affiliative design provides positive opportunities to enhance the natural sociability of people and other primates, encouraging them to enjoy each other's company. What could be more natural? What could be more important for building the early and lasting bonds needed to support the long-term survival of endangered primates and other species in our human-dominated world?” - Jon Coe "Increasing Affiliative Behaviour Between Zoo Animals and Zoo Visitors"

Affiliate Design

Rotation Design.

The most recent step in exhibit design is the rotation exhibit. Having various groups of animals transfer between different exhibit areas on a regular basis during the day can combine all the concepts of immersion design, themes, storylines and culture elements with activity-based training to add to the impact of zoo exhibits for both visitors and animals.

"Immersion exhibits have changed animal zoo exhibition using 'nature' as the model for international best practice, yet even the most diverse zoo habitats don't provide animals occupations and animals soon become habituated with resulting decrease in animal activity and visual interest for the public. At Louisville's (Kentucky USA) Islands Exhibits orang-utan, tapir, babirusa, siamang and Sumatran tiger rotate through four habitat areas on a randomly determined schedule. Five years of behavioural observations show normal stress levels, increased activity and previously unseen natural behaviours.”- Jon Coe "Mixed Species Rotation Exhibits"

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

|  |

Function.

function

ˈfʌŋ(k)ʃ(ə)n/

noun

noun : 1. an activity that is natural to or the purpose of a person or thing.

"bridges perform the function of providing access across water"

verb : 1. work or operate in a proper or particular way.

"her liver is functioning normally"

Even though function comes from the Latin “fungi” meaning to perform, it would seem more appropriate for describing activity than programme. However, the idea of function as a performed action has long been overtaken by its usage within the modern world. Functionalism is the study of ergonomic actions, involving measuring efficiencies and tolerances. What is important is that function never directly dictate design, but rather sets the conditions and parameters in which the creative limit of the project abide in.

Aesthetics simply, is the study of beauty. Specifically the reason to why we find something beautiful and the philosophy of whether beauty exists objectively. This makes it very similar to ethics , where both fields work hard to understand how humans decided whether or not the object in which they are observing falls into which category. Both of them concern value judgements and moral priorities and therefore unlike logic and some philosophies, aesthetics in not based on rules. Aesthetics and ethics are rather about balancing subjective and objective inputs in which results in a common personal decision.

In architecture, aesthetics concern how particular interests and desires become manifest as spatial strategies. For example, the Elephant House at Zurich Zoo and the Orang-Utan exhibit located at Perth Zoo, Australia.

Elephant House, Zurich Zoo

The Elephant House at Zurich Zoo by the Swiss firm Markus Schietsch Architekten. The Kaeng Krachan Elephant Park Zoo Zurich offers six times as much room as the previous enclosure, creating an environmentt where the elephants are able to roam freely between indoor and outdoor spaces. Markus Schietsch Architekten collaborate with landscape firm Lorenze Eugster and engineering office Walt + Gamarini on the project, creating a environment that can house up to 10 elephants at a time.

The building’s most prominent feature is its elaborate wooden grid shell interspersed with 271 ETFE plastic skylights - all in varying shapes and sizes, recreating the impression of light filtered by tree branches.

"The roof unfolds its atmospheric effect – as if through a canopy of trees, the sunlight filters through the intricate roof structure, generating constantly changing light atmospheres.”

The 11,000-square-metre complex boasts several different watering holes, allowing elephants to swim and bathe. There is also a pool with a glass wall, providing an underwater viewpoint for visitors to observe the animals swimming from a more unusual angle.

Giraffe House, Auckland Zoo

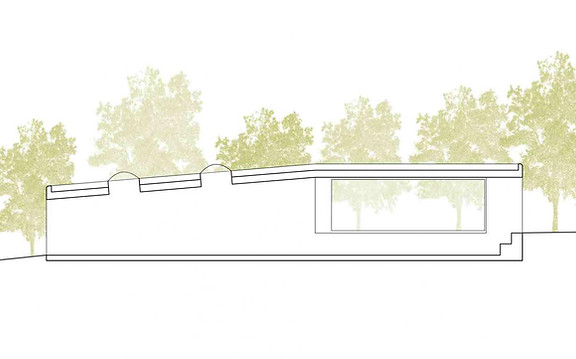

The Giraffe House at Auckland Zoo designed by Monk Mackenzie and Glamuzina Patterson, in addition to being aesthetically pleasing, offers a space to comfortably accommodate both its long-necked inhabitants and their human keepers. Although the slanting roof shapes give the building a slight chapel-like appearance, the reality is more carnal; the intersecting anatomy of these forms reflects one of the purposes of the house, which is to encourage the world’s tallest terrestrial mammals to copulate.

Flexibility was a primary objective of the shelter – due to the changing functional and physiological needs of the giraffe. Moveable doors and walls allow the space to be transformed. The four sliding exterior doors open to different yards that can be configured to allow for separate roaming areas for the giraffes. Keepers and vets use the mezzanine level to observe and interact with the giraffes. It also allows for small visitor groups to safely view the giraffes.

Analysis

Analysis

Programme within architecture is all the imagined activities that take place within a building. The word despite being used in this context, still remains the same definition as if it were to be used in biology or computing meaning the causes for a person or animal to behave in a predetermined way. Although programming when used in this context may sound sinister, the way in which some animals in nature behave the way they do is conceptually identical to descriptions of how humans organise their spaces and the movement within them. Like how we can dictate the operations of a computer, we can predetermine the possible behaviour of the population through designation and affordances of space.

Programming is a scaleless quality, often incorrectly called "function". A bedroom, bathroom, living room are all programmes describing the intended activities of the space, as well as determining the qualities and needs of furnishing in order to make these activities possible. It can be purposely vague to maximise possible activities like a hall or stadium however, it can fall under "narrative" architecture which is the design go imagined conditions and scenarios such as the Giraffe House at Auckland Zoo designed to provide the animals space to copulate and the Öhringen Petting Zoo in Germany where interaction between to resident animals and the visitors are much encouraged.

ZSL London Zoo Sumatran Tiger Enclosure

Another enclosure designed with the idea of recreating a stimulating arboreal-like environment for animals provided interpretation of their physiology, intelligence and habitat is the Orang-Utan Exhibit at Perth Zoo. This project designed by Iredale Pedersen Hook Architects created a facility that consists of an elevated broad walk, exhibit furniture to 7 exhibits as well as provided renovations to the interior of an existing building constructed in the 1970s including pneumatic access doors from the building to the exhibit habitats. Due to the inquisitive nature of Orang-Utans, it is critical that the habitat is able to provide a stimulating environment. A particular Orang-Utan, Hsing Hsing, who has been diagnosed with type-2 diabetes have shown significant improvement in his disease as well as becoming more active after living in the exhibit for a few weeks.

The nesting platforms are critical as orang-utans build nests in their natural habitat and need to be able to do the same at their home at the Perth Zoo. The nesting platforms also support drinking points and water canons that the orang-utans can spray each other with as a behavioural enrichment activity. The bases of the poles support cordial and jam dip tubes providing further stimulation for the orang-utans as they make tools to remove the food from the tubes.

This project was executed under these strong values of habitat and biodiversity conservation that informed all aspects of the design, from the detailed industrial design and performance of the animal habitats to the longevity and maintenance costs of the facility were considered. Most importantly was the need to communicate the message of conservation to visitors to the exhibit.

Orag-Utan Exhibit, Perth Zoo

Öhringen Petting Zoo, Germany

Designed by Kresings Architektur, the ensemble’s formal shape interacts strongly with its use as well as its urban context. The exposed site, situated right by a pond allows the two contrasting heights of the buildings in combination with the fence to be conveyed easily, offering views to visitors of all ages walking by to the petting zoo. In this manner, the buildings appear very much as a whole, however remain subdivided and delicate in the natural surroundings by the depth and complexity provided by it’s lamellar-like facade of the aviary and stable.

The construction and orientation of the buildings are particularly designed in response to the State Horticulture Show alongside the veterinary office in order to be able to keeping the animals ( alpacas, kangaroos and nidus ) in an environment as natural as possible.

The usage of larch wood is the one of the outcomes as a result of close cooperation with the veterinaries. The wood is not only resisted and therefore sustainable, it does not require to be treated , eliminating the danger of poisoning the animals.

When considering form, architectures have to take into account the difference between an infill building that fits tightly within its' site boundaries (leaving no unoccupied space on the site, except perhaps a defined outdoor courtyard) and a freestanding building located within a large expanse of parking. Without the aid of other space-defining forms such as trees, fences, level changes, and so forth, it is very difficult for a large space to be defined or satisfactorily articulated by most singular forms.

Shape, Mass/Scale, Scale and Proportion are some of the aspects that are to be taken into consideration in order to analyze or design an architectural form.

Shape :

-

Shape refers to the configuration of surfaces and edges of a two- or three-dimensional object. We perceive shape by contour or silhouette, rather than by detail.

-

Primary shapes, the circle, triangle, and square, are used to generate volumes known as "platonic solids." A circle generates the sphere and cylinder, the triangle produces the cone and pyramid, and the square forms the cube. Combinations of these platonic solids establish the basis for most architectural shapes and forms. Recent advances in digital technology have promoted the design and representation of more complex, non-platonic forms.

-

Volumetric shapes contain both solids and voids, or exteriors and interiors. Some shapes are formed through an additive process, while other shapes are conceptually subtracted from other solids.

-

Shape preferences may be culturally based or rooted in personal memory, or convention. For example, a dome or steeple may connote religious architecture in some cultures, while an American child's drawing of a house often depicts a square shape with pitched roof—a shape that many houses do not possess in our culture.

Mass/Scale :

Mass combines with shape to define form. Mass refers to the size or physical bulk of a building, and can be understood as the actual size, or size relative to context. This is where scale comes into play in our perception of mass.

-

Scale is not the same as size, but refers to relative size as perceived by the viewer. "Whenever the word scale is being used, something is being compared with something else." (Moore: 17) This relation is typically established between either familiar building elements (doors, stairs, handrails) or the human figure. Scale may be manipulated by the architect to make a building appear smaller or larger than its actual size. Multiple scales may exist within a single building façade, in order to achieve a higher level of visual complexity.

-

The term "human scale" is frequently used to describe building dimensions based on the size of the human body. Human scale is sometimes referred to as "anthropomorphic scale." Human scale may vary by culture and occupant age. For example, buildings occupied primarily by children, such as schools and child development centers, should be scaled in relation to the actual size of children.

Proportion :

In general, proportion in architecture refers to the relationship of one part to the other parts, and to the whole building. Numerous architectural proportioning systems have developed over time and in diverse cultures, but just a few specific examples are listed below.

-

Arithmetic: The Ancient Greeks used clear mathematical ratios for both visible and auditory phenomena, such as architecture and music. For instance, Pythagoras emphasized the importance of numbers. Originating in Antiquity, the "Golden Section" has been used by Renaissance theorists, modern and contemporary architects. The Golden Section or Golden Mean is both arithmetic and geometrical, and is prevalent in both the natural world and classical architectural design. It may be expressed as a:b = b (a+b). This relationship can be verbally described as: a is to b, as b is to the whole. The Golden Section is also apparent in the Fibonacci series of integers: 1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21,34,55, etc. Each succeeding number is the sum of two previous numbers. This series forms the basis for a spiral, as found in the snail's shell or the spiral volutes of ionic column capitals.

-

Geometric: In Classical architecture, the diameter of a classical column provided a unit of measurement that established all the dimensions of the building, from overall dimensions to fine detail. This system works for any size of building, since the column unit fluctuates while the internal relationships remain constant. Drawings of the "classical orders" explain this set of relationships geometrically.

-

Harmonic: The ancient discovery of harmonic proportion in music was translated to architectural proportion. For instance, this system posits that when the ratio of 1:2, 2:3, or 3:4 is applied to buildings or rooms, harmonious proportion results. The early Renaissance architect Alberti credited the harmony of Roman architecture and the universe to this system. The Renaissance architect Palladio, along with Venetian musical theorists, developed a more complex system of harmonic proportion based on the major and minor third—resulting in the ratio of 5:6 or 4:5

Research.

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

|  |

aesthetics

iːsˈθɛtɪks,ɛsˈθɛtɪks/

noun

noun: aesthetics; noun: esthetics

-

a set of principles concerned with the nature and appreciation of beauty.

-

the branch of philosophy which deals with questions of beauty and artistic taste.

-

The philosophy of aesthetics can be mastered by any designer if he follows these key elements listed below…

-

Mass and space

-

Proportion

-

Symmetry

-

Balance

-

Contrast

All these qualities are collectively important and can have an important impact on the design. However how beauty is perceived varies from one person to another, therefore making sure that architecture is functionally efficient is most important.

Aesthetics.

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

|  |

Programme.

programme

ˈprəʊɡram/

verb

verb: provide (a computer or other machine) with coded instructions for the automatic performance of a task.

"it is a simple matter to program the computer to recognize such symbols"

-

cause (a person or animal) to behave in a predetermined way.

"all members of a species are programmed to build nests in the same way"

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

|  |

Form.

form

fɔːm/

noun

noun : 1. the visible shape or configuration of something.

"the form, colour, and texture of the tree"

2. a particular way in which a thing exists or appears.

"essays in book form"

The final criteria that most architects take into consideration when designing and observing zoo architecture is form. Form in architecture is first of the all the plan drawing. It is the spatial articulation of functions, programme and aesthetics. Form is often conflated with style despite not being related. As have been previously discussed, style is an expression of ethics and therefore not intrinsically spatial. Form is only about space.

Analysis

Analysis

The importance of form is perhaps one of the most contentiously debated subjects in contemporary architectural discourse. The dictum “form follows function,” repeated over the century since its first articulation, is the symbolic nexus around which arguments pertaining to form have been organised ever since. It remains relevant only in so far as it is precisely the function of form that remains contested. The inherent contradiction of the “functionalist” argument lies in the incommensurate equation of specific architectural responses (forms) to abstract social behaviours. This contradiction is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of social “functions,” resulting in the over-generalisation of nuanced forms of cultural production (work, leisure, home), that simultaneously ignored the temporal dimension of social interaction – how different kinds of work, leisure and domestics change over time. Following this logic, the modernists were compelled to create highly generic spaces, like the office tower, which have proven insufficient both formally and functionally.

Consumed with the post-structuralist analysis of “texts,” the post-modernists emphasised the nature of architectural forms as cultural signifiers. The underlying argument of their work relied on re-interpreting the architectural lexicon in ways that created symbolic associations and fissures with the past. Labouring under the compendious critique of literary theorists, like Jacques Derrida, the post-modernists focused on systems of elision, through which cultural referents were utilised in ways that essentially problematised their ultimate meaning (or reading). This kind of highly semantic re-contextualisation was applied both to traditional, historically recognisable and/or popular architectural forms (Venturi), and to modernist forms alike (Peter Eisenman), and represents a re-orientation away from the “form follows function” paradigm of modernism, towards a ethos best articulated as “form follows meaning.” For example,

Modernism.

Rejecting over the top decoration and focusing more on minimalism, Modernism became the single most dominant movement in 20th-century architecture and design. This also meant an introduction into a new style and philosophy of architecture and design associated with a more analytical approach to the function of buildings, a strict, rational use of ( often new ) materials and an openness to structural innovation. This movement also encompasses Futurism, Constructivism, De Stijl and Bauhaus. The style is most known for its :

-

asymmetrical compositions

-

use of general cubic or cylindrical shapes

-

flat roofs

-

use of reinforced concrete

-

metal and glass frameworks often resulting in large windows in horizontal bands

-

an absence of ornament or mouldings

-

a tendency for white or cream render

Plans would be loosely arranged, often with open-plan interiors. Modernist buildings include the The Barcelona Pavilion designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) redesigned by aniguchi along with Kohn Pedersen Fox in 2004.

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

|  |

Exerts from The Zoo Enclosure Standards, Switzerland published 2001

Exerts from Containment Facilities Standard for Zoo Animals, New Zealand published 2007

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lion Gorge Melbourne Zoo

Due to the Sumatran tiger being one of the rarest subspecies of tiger with only approximately 300 individuals left in the wild, it was crucial that ZSL London Zoo create a new facility that will not only introduce a new breeding programme but create a space that allows experts to gain valuable information about the animals that can later be applied to conservation projects.

With the project bearing the pressure of being such global significance, there were a lot of elements to take into account when designing the new structure. The primary focus is of course on animal welfare, conservation and the creation of a habitat that is able to replicate the animals’ natural habitat - rather than the creation of an architectural masterpiece.

Our goal was to seek out the latest technologies and designs that could match our husbandry and habitat requirements while still satisfying visitor needs.’ - Robin Fitzgerald ( Project Manager )

Striking the balance of animal privacy and patron entertainment is a test. OLA and team with Melbourne Zoo just about perfect the process. A winding path wraps around multiple display ‘windows’ to provide framed views into the lion habitat creates a complete visual connection, allowing the animal to come right up to visitors, enabling that all-important emotional connection. Visitors and lions seeking respite from the elements can easily find shelter and private space.

“Built environments have been a part of exhibits for a long time but often disguised as mud, or rock-faces or themed to visually link the exhibit to a pre-conceived idea of primitive architecture of a region. We think a contemporary architectural approach helps to explain the reality of the conservation issues at hand. Architecture can become part of the education process and tool to help us better understand how to conserve various species.” - Phil Snowdon, principal at OLA architects

From a habitat perspective the zoo enclosure clearly needed generous proportions, especially in height - the Sumatran tiger is a keen climber with a preference for observing its terrain from a high vantage point and can boast an impressive vertical jumping ability of up to five metres.

“The project demanded a large, fully enclosed secure environment whose barrier was as invisible as possible. Standard building construction and engineering methods are not suitable for good zoo projects, the key is to adapt materials and technology to suit the purpose.” Mike Kozdon, Wharmby Kozdon Architects

The design concept for the new ape house picks up the characteristic themes of ridge, valley and forest. The new enclosure for African apes is situated at the highest topographical point of the landscape park and takes the form of an artificial ridge. The building twists in an S-shape between the existing stock of mature trees, and appears to burrow into the ground at its curving ends. This impression is created by two greened, curving, shell-like roof surfaces that rise to a height of 7.5 metres out of the neighbouring landscape park. These two skins, which meet to form the mountain ridge, house an enclosure for gorillas on one side and an enclosure for bonobos on the other. A pathway for visitors leads between the two indoor enclosures with room-high glazing affording a view over the neighbouring landscape. The monolithic appearance of the concrete construction of the indoor enclosures inside the “mountain ridge” contrasts with the open, greened system of outdoor enclosures that are fashioned as a natural extension of the greened roofscape and are covered in part by a lightweight steel mesh construction.

The lightweight net of steel mesh is carried by a “forest” made of slender, inclined steel columns. The construction serves as a system of artificial tree trunks that the bonobos can climb up and rest on. Artificial lianas, hammocks and sleeping nests slung from the roof supports serve as branches in the forest canopy. The interleaved arrangement of outdoor and indoor enclosures, and of topography and building, results in a structure that is a harmonious part of the landscape.

The terraced outdoor enclosures have been designed as a near-natural counterpart to the indoor enclosures. The bonobo enclosures are covered by a wire mesh and contain shrubbery, climbing plants and trees that provide the apes with more secluded spots that they can withdraw to.

The outdoor enclosures for the gorillas have been designed as an expansive open natural landscape. The existing trees in the park have been incorporated into the enclosure and their extensive canopies provide natural shade for the primates. An artificial rocky landscape at the rear forms a boundary. By augmenting the existing trees with trunks to climb on, watercourses, shallow pools, marshy areas and a ditch, the outdoor enclosure corresponds to the diverse topography of the gorillas’ natural, wooded habitat.

Mood Board.

Functionalism is the study of ergonomic actions, involving measuring efficiencies and tolerances. A function has gradually become purely mathematic. For example, describing a kitchen as a functional space would be to assume that the kitchen is a function of cooking. Such statement obviously does not make sense as cooking is the “aphorism for all possible parameters implicated in making meals” and the kitchen only acts as a space that allows such action to happen. Without it, people are still able to cook outdoors. As a result of such distortion of the meaning of the word function, it would be more accurate to say that cooking is the programme of the kitchen, not the function.

Today, when we look at a building’s function we must take into account all the invisible parameters that cause it to exist not only just the concerning its occupancy. Finance, planning, regulations, standards and environmental factors are all functional parameters that influence programme and form.

For example, durning the time that the modernist movement was receiving a lot of attention, the ideology that form follows function was also caught on. This paired with the advances in medical studies and desire for sterilisation produced zoo exhibits that were easy to clean. This meant concrete everywhere.

Since the mid-20 century, the environment awareness and human right ethics has become more wildly known, giving way to animal rights as well. In 1950, Hediger wrote “Wild Animals in Captivity” which opened the public’s eyes to the idea of practices and exhibit design based on an animal’s natural history. As well as advances in healthcare, animals in captivity began to be treated for both physical and mental health.

As soon as Sinead explained the Report and the various styles in which a could write my report, I knew almost instantly that I wanted to write my report on Zoo Architecture. With Zoo architecture covering a wide variety of topics with lots of elements to consider , I knew that I had to narrow my subject down in order to be able to comfortably explore and analyse the subject within the 5000 words limit. In order to do this, I have decided to come up with a question that I will discuss throughout the report. I have chosen to write about Zoo Architecture as I, myself work at a zoo and despite all of the good things the zoo has done, I feel that some enclosure designs are ought to be re-visited to improve the quality of living of the animals inhabiting that enclosure. Therefore, the question " How does the function of the Zoo implement Zoo design" is something I would like to explore further within my report.

Over the years, exhibits have become more and more 'authentic' with the rise of animal welfare. Zurich zoo's ELephant house for example, tries to replicate the aesthetics found in nature by creating an elaborate wooden lattice littered with over 270 ETFE skylights to recreate the effect of sunlight filtering through branches, whereas the Orang-Utan enclosure tries to recreate the function as well as the aesthetics of an arboreal-like environment via nesting platforms and ropes that allow the animals to easily manuver around the exhibit. Both enclosures even though are considered architectural masterpieces, their main priority is to closely simulate the wild in order to make its residents feel as home as possible.

Above all, the Programme concerns what the building is built to do or how the building can provide space for a specific use. For example, the Giraffe House at Auckland Zoo even though very structurally pleasing, is not only built for its 6 metre giants with a a slanting roof that mimics the natural built of the animals, encouraging them to copulate but also for the caretakers by providing a place where the they can closely monitor the gentle giants without feeling threatened.In the same way, the Öhringen Petting Zoo are built with the goal of encouraging interaction between animal and human in mind therefore every littler detail right down to the building materials used are not only sustainable but they require no treatment therefore eliminating any danger of poisoning the animals and visitors alike . As you can see, both facilities are designed and built with a specific purpose in mind therefore in these cases, Programme determines Design.

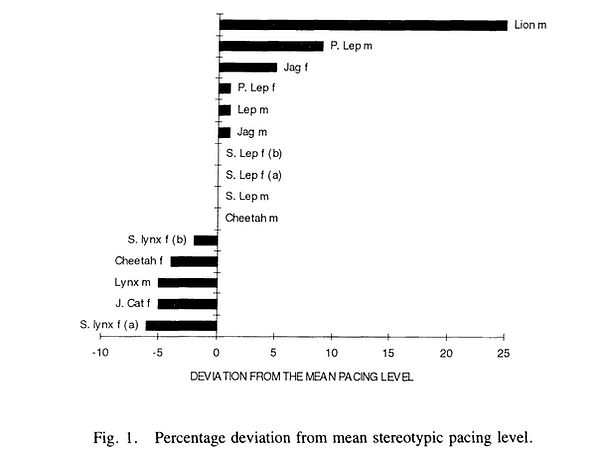

Function of a building, even though use to be very similar if no the same as the programme, now concerns more about the outside factors and how they have impacted and determined the design of the exhibits. Factors such as The Zoo Enclosure Standards published by Switzerland in 2001 and The Containment Facilities Standard for Zoo Animals published later in 2007 are only a small part in which Zoos have to take into account when housing and recreating a habitat for its residents. All of this started when the Modernism Movement triggered a rise in not only in human right ethics but also a rise in animal welfare as well. There has also been scientists and animal behaviourists here and there conducting studies and papers concerning the change of various species’ behaviour when kept in captivity, one in which are felids. Due to their natural “stalking” behaviour, it is quite challenging to be able to recreate an exhibit that allows the animals as much stimulant as its wild counterpart, not only physically but psychologically. Therefore, which such detailed study made, Zoos can now provide stimulating exhibits as well as develop existing exhibits for their residents that will make them feel at home in such an unnatural environment.

Last but not least, the Form of a building explores the physical bulk of the building ( i.e its actual size relative to its context ) as well as its relationship in regards of it surrounding environment. There are throw main element in which architectures take into account when designing a building - Shape, Mass/Scale and Proportion. In recent years buildings concerning nature such as Zoo exhibits and Conservation facilities are built to blend into its surroundings whilst still provided a safe and secure environments for its residents leading to an increase use of materials such as steel mesh where despite its unimposing appearance, creates a very strong barrier protecting its inhabitants.

Enclosure for African Apes, Wilhelma Zoo

“Setting the glass as a barrier to the impact of a fully grown lion was probably the biggest challenge. We had a facade engineer calculate the impact of a lion running full steam into the glass. This resulted in Viridian manufacturing a custom make up of various sheets of interlayers and glass. The visitor cannot read the thickness and so we hope they will feel a little vulnerable at times.”

- Phil Snowden when asked about design challenges

Wildlife Observation Pavilion Zoo Berne

The new Wildlife observation Pavilion at Bern Zoo is situated amongst mature trees and the existing animal enclosures. Like an animal skin, the golden-green shimmering mosaic façade clings to the exterior walls and the roof, while the interiors continue the metaphor with their dark-red tones. Large gold-framed observation windows open out onto the woods and the zoo enclosures. A covered shelter serves multiple uses, providing a place for jazz matinees or barbecue parties as well as a weather-protected location from which visitors can observe wolves, marmots and small mammals. Family-friendly and disabled toilets, accessible for all zoo visitors from the park’s main promenade, complete the pavilion.

The Lion department is a new addition to the Safari Park , opened in 2017.The department is home to 20 lions, 16 females and 4 males. The Lion Department falls under the Tiger Department and uses what used to be Zone 1 Tiger Enclosure to house the new residents. Therefore I thought that it will be interesting to study to lions alongside the tigers to see how the enclosure design caters to its new inhabitants.

Brief Background on African Lions.

The Lion Department.

Size :

-

1.40 metres to 2.50 metres

Weight :

-

Top Speed : 35 mph

Diet :

-

Carnivore

-

Natural Prey : Antelope, Warthog, Zebra

-

Unlike other felines, Lions are not solitary hunters but instead the Lionesses work together in order to chase down and catch their prey with each female having a different strategic role.

-

This strategy allows them to kill animals that are both faster and much larger than they are including Buffalo, Wildebeest and even Giraffe. Depending on the abundance and variety of prey species within their territory, Lions primarily catch Gazelle, Zebra and Warthog along with a number of Antelope species by following the herds across the open grasslands.

Behaviour :

-

Lives in small groups called prides

-

A pride is made up of 5-15 related females and their cubs along with a generally single male (small groups of 2 or 3 though are not uncommon).

-

-

Very Social with distinct hierarchies within the prides

-

Females are usually the ones out hunting

-

The Lionesses in the pride hunt together meaning that they are not only more successful on their trips, but they are also able to catch and kill animals that are both faster than them and much bigger.

-

-

The Males will look after their young

-

Due to their enormous size, male Lions actually do hardly any of the hunting as they are often slower and more easily seen than their female counterparts.

-

Preliminary Evaluation of Environmental Enrichment Techniques for African Lions by D.M Powell.

Continuing from my summary of Summary of The Effects of the Captive Environment on Tiger Behavior as stated in Wild Tigers in Captivity: A Study of the Effects of the Captive Environment on Tiger Behaviour by Leigh Elizabeth Pitsko , I wanted to try and find another study paper that were specifically done on African Lions. Even though African Lions and Tigers both fall under the category of felids, they are very different both physically and behaviourally. In addition to results found in prior studies, introducing new food sources and alternative methods of food presentation were found to associated with increased activity and increased behavioural diversity as well as complexity. Enrichment has also led to increased use of exhibit space and decreased abnormal behaviour. Furthermore, enrichment has also been found to educate visitors. An exhibit that stimulates the animal’s natural environment as well as those that provide enrichment for their residents appear to be very well-received amongst visitors. For example, due to an increase in zoo staff and visitor interaction, the visitors seem to appreciate the efforts made in zoo to provide suitable environments for their animals more.

African Lions are harder to cater for in terms of enrichment and overall exhibit furnishing as in the wild, lions are inactive for an average of 20 - 21 hours per day, with two hours spent travelling through their pride’s territory and around 40 - 50 minutes of the day eating. However, hunting in the wild is not always successful and therefore feedings may be up to several days apart. Furthermore, as lions are social animals and a pride of typical lions may contain up to 15 members, most Zoos do not have the facilities or the funds to house an entire pride of lions, which in turns limits opportunities for these lions to demonstrate complex social behaviours that are often observed in the wild. Enrichment for these big cats must not only be intriguing but also durable and safe. Included within this study was an experiment done on four African lions, a pair of adults ( one being a seven-year-old male, the other, a six year-old female ) and a pair of subadult males. While the adults were captive-born and reared in the United States, the subadult males are captive-born in South Africa and brought over to the United States when they were three years old. The adults and the juvenile lions were kept separately and will be placed on exhibit on alternative days. The enclosure is designed to simulate the kopjes or rocky outcroppings on the African Savannah and when the lions are off exhibit, the animals have access to their night cages as well as two outdoor patios (3.38 X 1.95 X 1.17 M and 2.60 X 1.95 X 1.17 M ). While the indoor holding areas included elevated resting platform, the outdoor patios contained large logs on the floor with both areas having sources of freshwater available. Prior to data collection, both holding facilities are cleaned in order to eliminate distractions to the lions. All lions were fed at around 5 pm each day in weekly intervals, with the adults receiving approximately 3.10 KG of chopped horse meat and the cubs receiving approximately 1.40 KG of meat.

Zoos commonly provide their residents large blocks of ice that may or may not contain food within them. However, in a lot of cases, the blocks of ice are not manipulatable due to their size and shape , therefore the lions can only sit and lick the ice until the food inside becomes attainable. With this in mind, Powell thought that it may be different and interesting to provide the lions objects that they actually can manipulate by pushing the enrichment around the enclosure with their paws. The first of the enrichment provided were circular ice blocks containing a small frozen fish in it. The second of the enrichment included musk cologne ( chosen due to it being an animal-based scent ), peppermint extract ( chosen for its botanical relation to catnip ) , allspice and almond extract ( both chosen due to their strong odour and history of being used at other zoos ). These scents were then used separately at four randomly chosen locations within the enclosure. The third enrichment was hanging logs from the overhead cage mesh. These logs were used as they are part of the permanent enclosure furniture and hence receives little use as a result of the animal haven grown accustomed to it. However, due to time related limitations, the logs were not given to the juvenile males during this study. The Enrichments are presented in a largely random sequence as individual items become available at differentiating points throughout the study. The adult lions were also kept off exhibit for a span of seven days in the earlier stages of the study due to the lions showing signs of stress due to high temperatures. Therefore as a result of this minor alterations, enrichment items are being presented repeatedly on consecutive days.

The data was collected by observing the animals for two 30 minute intervals daily during the 24 days at 13:30 pm and 15:30 pm. These time intervals corresponded to periods of low keeper activity in the area. The first observation period was a baseline period in which no enrichments were present. Prior to the second observation, enrichment items were placed on patio 1. The observation period will then begin after the lions are given access back into the enclosure containing the enrichment. During these observations, the enclosure is also scanned repeatedly in 20 second intervals, with every tenth scan the location of the lions is recorded and a behaviour from the ethogram was recorded for each animal.

After processing all data collected, the actions, licking/gnawing , paw manipulation and sniffing/flehmen showed significant differences between the baseline and enriched condition in the adult lions. Licking and gnawing as well as paw manipulation increased significantly over baseline when ice was presenting whilst sniffing and flehmen increased significantly when the scents were placed in the enclosure. Paw manipulation also increased significantly when hanging logs were present. In cubs, these actions showed significant differences across all treatments with all of these behaviours increasing significantly when the ice containing fish is presented. Sniffing and Flehmen also increased significantly when scents were placed in the enclosure.

In conclusion, the different enrichment techniques had a roughly equal effect on the behaviour of the animals, with the frozen balls of ice eliciting most changes in the lions’ behaviour. However, even though the lions seemed to push the ice balls around until the ice has shattered, the fish inside were only eaten on one occasion, Even though several of the behaviours showed dramatic increases, the difference between the two groups of data failed to reach statistical significance. All of these enrichment techniques tested out brought a positive change in the behaviour of the lions. In particular, the lions appeared more alert and active and used more of the available enclosure space. Of all the scents used, peppermint extract received the strongest responses - this may be due to its botanical relations to catnip. The results from this study suggest that different types of enrichment will produce different changes in behaviour. This also emphasises the need for novel stimuli and manipulatable objects. The animals are likely to be stimulated only by objects that are alien to their daily care taking routine and may interact more with objects that are manipulatable. These enrichments provided should also take advantage of as many of the animal’s senses as possible instead of focusing on food.

Studying Dolphin Behaviour in a Semi-Natual Marine Enclosure : Couldn't we do it all in the Wild? by Amir Perelberg

The facility in which is study is conducted is located in a tower about 8 metres above a 14,000m2 continuous semi-natural marine enclosure, the “Dolphin-Reef” tourist facility. The site is at south of Eilat, Israel located at the northern part of the Gulf of Aqaba, the Red Sea. The dolphin group in which this study is done on was consisted in 1990 and included two males and three females brought from Taman Bay. Ever since, the dolphin group as varied due to new births, deaths and a translocation of three dolphins back to the Black Sea. Individual identification of the animals is based on distinct shapes, marks of dorsal fins, body size, girth, colour and individual body marks. This arrangement in which all age and gender classes live together in a single enclosure allowed a study of influences of social relationships and of the tendency of the dolphins to conduct cooperative behaviour to be done by staff.

The enclosure includes a sandy bottom marine habitat, scattered patches of sea grass beds and coral knolls and enriched with several artificial reef constructions. The bottom of the site gradually slopes from shore to about 15-20 metres depth along a plastic net, allowing sea water to flow through freely and marine organisms such as fish, cephalopods, jellyfish and sea turtles to enter the site. From 1997 to 2202, one or two underwater gates were open allowing unlimited access to the sea 24 hours a day, all year round. Most males ( adult and adolescent ) and the adolescent females frequently went into the open sea and have always returned back to the facility. However, during this period there were one adolescent male who went on a 9 day excursion. He was then later identifies at Dahab, about 125 km to the south of the site. All other excursions lasted less than a day. Unfortunately, due to unsupervised encounters between humans and dolphins along public beaches where humans would harass dolphins resulted in aggressive dolphin behaviours and therefore, the gates were closed and the dolphins were confined to the site ever since.

This non-subdivided enclosure allows the animals unrestricted social interactions and associations among all ages and genders. The animals prey on fish and invertebrates inside the enclosure as a supplement of daily feeding and an expression of their natural behaviours. The primary source of food comes from artificial feeding, where the dolphins will be fed by the trainers 5 times a day ( at 9:00, 10:00, 12:00, 14:00 and 16:00 pm). The morning feeding is off limits to the public and allows the staff to monitor the dolphin’s health and train the dolphins in preparation for medical procedures. The feeding is not contingent on performing any behaviours for show, the animals never display any show related behaviours during feeding time. During these feeding times, three fully guided and supervised programs are conducted. Swimming with the dolphins, diving with the dolphins and dolphin assisted therapy. Participation by the dolphins in all of these programs are completely voluntary and the animals are free to approach any person as well as have free access to larger shelter areas within the enclosure, away from all visitors. Tourists, on the other hand are not permitted to chase after, harass or touch the animals. Training sessions are also performed after feedings as an attraction and as a means of environmental as well as social enrichment for the animals. Dolphin participation to these activities are completely voluntary and food is never used as a reward.

The bottle-nose dolphin is known as a highly social species in which cooperative behaviours construct a large part of its behavioural repertoire. These behaviours include communal foraging and hunting, defence against predators and conspecifics, vigilance sharing, alliances for mating purposes and play behaviours.

The facility

An Echolocation Visualisation and Interface System for dolphin Research by Mats Amundin

As I’ve noticed an ongoing pattern that runs in all of the studies conducted where the enrichments used are of very similar nature which as a result, produce very similar conclusions. I have decided to find a new way in which researchers have used the animal’s natural behaviour and capability to provide enrichment as most animals such as the bottle-nose dolphins are highly intelligent and complex, therefore it would only be suiting if the enclosure in which they are kept are able to provide stimuli that can satisfy these behaviour not only physically but psychologically as well.

Although dolphins are known for using their rostrum to touch and manipulate objects, it was deemed of more interest to explore and study their main sensory system- their sonar. Dolphins have gone through extensive evolution and as a result of this, the animals have developed very advanced active sonar system based on the development of a unique sound generation and detection system. The ELVIS project i.e. the Echolocation Visualisation and Interface System is developed in order to explore the animals' sonar to its full dynamic potential. This project, designed by Mats Amudin, consisted of a matrix of hydrophones attached to a semi-transparent screen lowered in front of an acrylic panel in the dolphin pool and when a dolphin aims it sonar beam at the screen, the hydrophones will measure the received sound levels. Which are then transferred to a computer where they will be translated into a video image that corresponds to the dynamic sound pressure variations in the sonar beam and the location of the beam axis. Connected to all of the above was also a projection in which the image representing the location of the dolphin’s sonar beam is projected onto the back of the screen, allowing the dolphin immediate visual feedback to its sonar output.

When the screen was first presented to the dolphins, showing all sound pressure level variations within their sonar beam, they spontaneously and deliberately explored it with their echolocation. There reactions were a result of being intrigued and stimulated by the visual feedback of their sonar beams. Through this project, the researchers were able to investigate the dolphin’s ability to associate sounds with visual stimuli.

Stereotypic behaviour, a pattern of movement such as pacing and head bobbing that is performed repeatedly, relatively irrelevant in form and has no apparent function or goal are really seen performed by wild animals therefore re often considered an indication of stress. These behaviours are often a result of an accumulation of causes for example, these behaviours may arise when an animal is physically restrained from moving to a desired place. Stereotypies may also stem from other behavioural or psychological stresses such as boredom, physical restraint, fear or frustration.

Limitation of space may be one of the causes of stereotypic behaviour. Most commonly, animals are more likely to be seen performing such behaviours in smaller enclosures relative to tiger enclosures. However, it is quite difficult to determine the exact amount of space an animal needs to avoid developing stereotypic behaviours.

Low stimulus diversity is also another cause touched upon in this study. Sterile environments as a result of the rise of animal welfare in the late 20th century are more likely to house animals that often appear “bored” or lethargic due to a lack of stimulation. These unusual substrates, in this case concrete, often result in common stereotypes in felids include pacing, head-twisting, tail and toe sucking and fur plucking and causes the animals to develop sore footpads as well as leg injuries. According to Sheperdson et al. ( 1998 ) environment enrichment “is an animal husbandry principle that seeks to engage the qualities of captive animal care by identifying and providing environment stimuli necessary for optimal psychological and physiological well-being”. This includes a wide variety of techniques. In particular, food can be hidden throughout the enclosure to encourage and entice the animals to perform hunting behaviours; wood blocks or logs may also be provided to satisfy felid scratching behaviour in the absence of trees. Furthermore, stimulating scents can be spread throughout the exhibit and sterile concrete enclosures can be replaced with natural substrate and vegetation. These elements are key as the provide for the well-being of animals therefore allowing the animals to display “natural” behaviours as well as increase reproductive success. Poole ( 1998 ) explains that the captive environment should be sufficiently complex to allow for a full range of locomotor activities including walking, climbing and swimming. In the wild, a mammal chooses a living area that offers suitable facilities that caters for its needs therefore, the same should be done in the captive environment. Carlstead ( 1998 ) illustrates that the more complex and unpredictable the environment is, the less stereotypic behaviour the animals preform. By providing stimuli, the tiger’s desire to perform a negative behaviour is lessened ( Carlsbad, 1998 ).

When planning for environmental enrichment, scale, vertical spacing and horizontal spacing are crucial factors that must be considered. All aspects of the natural environment should be included in the captive enclosure and by planning by scale, it is made sure that this criteria is met ( Seidensticker and Forthman, 1998 ). Vertical and horizontal spacing including height, levels and angles are also elements to be considered in planning zoo exhibits as they are a part of the “natural” world which is often left out of exhibit design. Deroo ( 1993 ) emphasises the importance of vertical and horizontal spacing , as “ space can be used to create a safe, enriching environment that encourages and rewards natural behaviour..[A] boulder, an incline, a well-placed tree or stream can give an animal illusion of space, as well as the distance it needs from other animals.” Felids live in complex and unpredictable three-dimensional habitats which should be replicated in their unnatural counterpart. Lyons et al. ( 1997 ) found a significant between relative enclosure size and average apparent movement in captive felids. A “large’ space, in this case being >45.7m x 36.5 m, provides the animals with the opportunity to run, stalk, chase and play. Such behaviours allow the animals to fully exercise their muscles and expend energy, which they would normally spend on hunting in the wild.

The presence of vegetation also creates a more natural environment for captive animals by providing hiding areas away from the visual presence of visitors and creating areas of shade ( Law et al., 1997 ). Vegetation also attracts insects and birds into the exhibit, allowing for a more complex environment. In the same way, pool availability are also key as tigers a avid swimmers and by providing a pond for them to swim in, we are encourage an alternate form of exercise and enrichment ( Bush et al., 2002 )

The concept of “environmental enrichment” involves providing captive animals with items that stimulate exploratory behaviours ( Lyons et al., 1997 ). Such items may be fixed in the enclosure such as sticks, ledges, waterfalls, balls and ice blocks. Enrichment furnishings are thought to improve the quality of life in captive animals. For example, stereotypic pacing in captive leopard cats significantly decreased after the enclosure was made more complex.

Last but not least, the visual presence of visitors should be taken into account when planning an exhibit as the presence of visits can influence the behaviour of the animals. For example, large crowds may cause animals to become nervous or agitated and therefore may drastically change their behaviours.

Wild Tigers in Captivity: A Study of the Effects of the Captive Environment on Tiger Behavior by Leigh Elizabeth Pitsko

Keeping felids within captivity has always been a controversial topic of discussion as some believe that felids belong in the wild. However, recent studies have shown the decrease of Bengal tigers from around 100,000 in 2000 to just 3,900 in 2014. This alarming drop in wild tiger population is caused by three main factors ; the decrease in prey, tiger-human conflict and the black trades market. Due to depleting forest areas, herds of wild animals such as deer as forced to migrate into other areas of land that unfortunately may be already preoccupied by humans. Tigers are known to migrate after these herds of prey therefore leading to a high chance of human-tiger conflict. However, as tigers are an adaptable animal, many have learnt to stray far away from humans and therefore survive alongside humans. However, a number of tigers unfortunately do encounter humans.

Abnormal behaviours, such as pacing, may develop in places where the human-made environment is insufficient and restrictive of the animals carrying out there natural of instinctive behaviours. Felids have very large home ranges within the wild and carry out "hide, stalk and chase" behaviours. Captive environments however, are not able to provide such circumstances due to spatial constraints and negative human reactions to predatory behaviours.

Normal behaviours can be defined as "the exhibition of a phenotypic trait within the environmental context for which primary selective forces have shaped it, the outcome of which being maximal, inclusive fitness." However, these behaviours are often replaced by abnormal behaviours due to lack of stimuli and space.

As there were a lot of controversy surrounding whether or not zoos and sanctuaries should provide live prey for captive tigers, I have decided to ask my friends of Facebook whether or not they agree and why. These were their answers.

"It's like if u r running away from a murderer in a gated area. There is no chance of survival, just kill the damn thing first dont torture it."

"I'd feel really conflicted about it. On one hand its enrichment for the tiger and recreating what it would do naturally in the wild. On the other hand yes an animal as to die for the tiger to eat but it could be done in a humane way without stressing out the animal (which would be not providing it live for the tiger to hunt)"

"1. Yes 2. That's what's tiger suppose to do in their natural environment"

"No, there are other forms of enrichment designed to mimic hunting it's not as if the tigers are in their natural environment anyway (they don't have the same drive to hunt as they've got regular feeding) so they're more likely to play with prey than end it quickly. If you can eliminate suffering on one part (i.e. the prey in this case) then why wouldn't you?"

"First response says no. Like other answers, I do support any movement or effort to mimic endangered animals habitat's in zoos but I think to put real animals into a situation where they will inevitably die is cruel"

"I don't agree unless the zoo is big enough to have an open space which I doubt."

"Yes, normal food chain in controlled environment"

As you can see, this is not black and white question. A lot of people were torn between their personal morals and wanting to allow nature to follow its course. However some do value their morals and therefore view such act as cruelty.

Views regarding Zoos Providing Tigers with Live Prey - Survey conducted on friends and family.

Feeding Live Prey to Zoo Animals:

Response of Zoo Visitors in Switzerland by Lauren Cottle

Apart from asking my friends on Facebook about whether or not providing live prey to felids to captivity is ethically correct, I also wanted to branch out and find answers for the same questions but from Zoo visitors of a different background. I wanted to do this because I feel like different cultural backgrounds may induct different morals and therefore by questioning an additional group of people with either a different religion, age or gender will be able to inform me on how different Zoo visitors view feeding live prey to Zoo Animals. Modern zoos as of recent, have been increasingly more concerned about being able to provide adequate conditions in order to reproduce and form stable populations, with the ultimate goal of reintroducing these animals back into the wild. In order to make these reintroductions successful, the animal’s social structure, survival skills. foraging and hunting skills must be maintained. Many deaths of reintroduced animals are due to behavioural deficiencies as generations in captivity make animals lose crucial learned attributes. Specifically carnivores as the constant supply of ready-made fodder can cause the loss of their hunting skills, resulting consequently in carnivores that are reintroduced into the wild four-times more likely to die of starvation than if they were introduced from other locations.

This specific study was done in 2007, with the help of a written questionnaire on 409 ( 207 men and 202 women ) visitors during their visit to the zoological garden of Zurich, Switzerland. All study participants were chosen at random , however, still maintaining the balance for sex and age by asking an equal proportion of men and women as well as people from varying age groups to participate ( 12 to 85 ). They were introduced to the idea of feeding live insects to lizards, live fish to otter, and live rabbits to tigers. A comparable study has been made earlier in 1995 at Edinburgh Zoo where it was found that both on and off exhibit feeding of live insects to lizards and live fish to penguins was accepted by at least 70% of the participants and only 32% accepted the feeding of live rabbits to cheetahs. Moreover, off-exhibit feeding was more appreciated than on-exhibit feeding. In addition to answering the questions included within the questionnaire, participants were also asked to state their age and gender as well as their highest level of education ( primary school, secondary school, apprenticeship, high school or equivalent, college) and from these categories, a data variable was derived indicating whether a person had a lower ( primary school up to apprenticeship ) or a higher ( high school and university ) education. Furthermore, they were also asked whether or not they owned a pet and, if so, which kind of pet. If any additional comments were made by study participants, they were also recorded.

With the exception of feeding rabbits to tigers on-exhibit, most participants agreed with the feeding of live grey to zoo animals, both on and off exhibit. The results in the cases of feeding live insects to lizards and live fish to otters did not differ significantly in their agreement to on and off exhibit demonstrations, whereas in the case of feeding live rabbits to tigers, the participants more often agreed to off-exhibit feeding. In the models only gender, level of education and frequency of visits to the zoo influenced the agreement of the participants to the idea of feeding live prey. Age, pet ownership and other zoo visits on the other hand, had no influence on their views. From the data, men agreed more with the on-exhibit feeing of live insects to lizards and live rabbits to tigers and study participants with a higher education more often agreed with the feeding of live prey off-exhibit. Frequent visitors to the zoological garden agreed less often than others with the on-exhibit feeing of live rabbits to tigers and agreed more often to the off-exhibit feeding of live fish to otters. Pet ownership in general did not do much in terms of influencing visitor’s opinion however, more of the study participants who owned a rabbit disagreed with the on-exhibit feeding of rabbits to tigers (72%) whereas only 50% of other participants that owned a different pet ( cat, dog ) disagreed.

Some participants, in order to justify their opinion made comments such as “it is natural” and “in nature, it is normal”. A “hierarchy of concern” , a function of the distance of relationship between the prey animal and primates, can also influence participants’ opinions as the results found also consisted with this idea. The closer the prey animal was related to primates, the fewer participants agreed that said animal should be fed alive to zoo animals or, if so, should be done off-exhibit. Humans like visually attractive animals with considerable intelligence and the capacity for social bonding and tend to avoid invertebrates due to their small size and behaviour that is unlike humans. Therefore, it is not surprising that the results of the questionnaire revealed that the participants were least concerned about the feeding of live insects and is most concerned about the feeding of live rabbits, especially on-exhibit. Furthermore, women objected more often than men which may partly be due to a greater emotional affection of women for attractive, primarily domestic pet animals.

In comparison to a study done in 1995 at Edinburgh Zoo, zoo visitors in Switzerland were more often in favour of the live feeding of vertebrates. However, rather than the difference between the results be due to culture-related differences, the difference of results may be due to an attitude shift caused by an increase knowledge about conservation issues and more exposure to predation events on nature documentaries that may have increased their habituation to seeing feeding of live prey on-exhibit. It is therefore possible that visitors may perceive on-exhibit feeding as an attraction and an opportunity to see the animals.

Influence of social upbringing on the activity pattern of captive lion cubs: Benefits of behavioural enrichment by Sibonokuhle Ncube

Effects of Pool Size on Free-Choice Selections by Atlantic Bottlenosed Dolphins at One Zoo Facility by Melissa R. Shyan

Due to dolphin pool designs that often stem from the concept that cetaceans are ocean based and ipso factor should live in open, deep, watery environments, there appears to be a trend in regulations concerning pool sizes for captive cetaceans, driving by the theory that “bigger is better”. This emotionally appealing rationale that came from the idea that cetaceans are marine animals, ocean-based species who ipso facts live in wide, open, deep watery spaces although emotionally appealing, is not data driven. In fact, habitat in the ocean differ as much as those on land. This study concerns the indue of captive environment sizes for Atlantic bottlenose dolphins ( Tursiops truncatus ), specially pool dimensions. Unfortunately, only a few scientific publications mentioned the characteristics of the environment in which Tursiops are found. In their studies of the residential pods found in the Sarasota Bay area, Irvine and Wells (1972); Irvine, Scott, Wells, Kaufmann (1981); and Wells, Irvine and Scott (1980) found this population in six different physiographic subdivisions of habitat. These include narrow and shallow waterways 2-3 metres deep, flats and shallows less than 2 metres deep, wide bays 2-5 metres deep, passages between areas that were 2-11 metres deep as well as off-shore areas less than 2 metres deep. Most sightings revealed animals in areas less than 3 metres deep. This indicates that the dolphins resided in the shallower areas ( approximately 2 metres deeps ) and moved to deeper areas predominantly for feeding and when resources are less available in shallower areas. Therefore, for Trursiops, it is possible that bigger is not necessarily better. Indeed, these reports indicate that in the wild, these bottlenose dolphins may frequent shallower, more than deeper waters. Few studies have been done on this species’ preferences for pool sizes in captive environments. Anecdotal reports from keepers, trainers and other marine mammal professionals suggest that when given a choice, bottlenose dolphins tend to stay in shallower pool environments. This study aims to test the hypothesis that the dolphins would tend to stay in pools and areas more similar to their natural habitat ( i.e. the shallower pool areas). It is necessary to recognise the limitations of this study. Across pools, it is not possible to control underwater noise differences, ambient light, volume of water and any conditioned associations that the dolphins may have developed over the years. For example, the Medical Pool is associated with the separation from conspecifics and uncomfortable medical procedures and thus, although the shallowest pool, may be of less preferred environment for the animals.

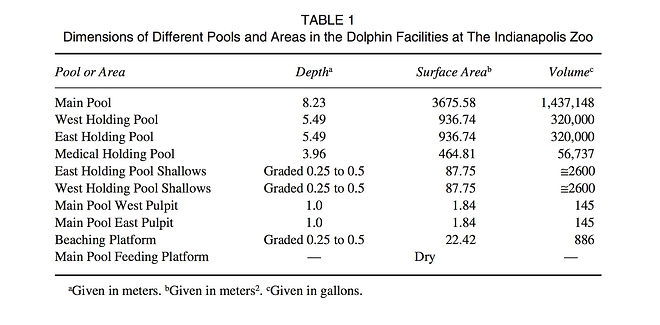

At the time of study (1996), two male and five female Atlantic Bottlenose dolphins at the Indianapolis Zoo were approximately 12 years of age. They all originated from the Gulf of Mexico, taken from the resident population at Pine Island Sound, Florida, a region similar in topography to Sarasota Bay where Wells and Hoffman (1997) did their wild population studies. The dolphins are a well established pod acclimated to the facility and to each other as a result of being introduced since 1988 and maintained at the zoo since 1989. The facility is an indoor facility housed in the Whale/Dolphin Pavilion. It is lighted by both artificial and natural lighting through large windows high up on the south wall. During early evenings, the facility has supplementary lighting supplied by large floodlights aimed at the ceiling of the pavilion. These floodlights are mounted 12.2 metres above the pools. The facility consists of four pools ranging in depths in strict increments of 3.96 m, 5.49 m and 8.23 m with five peripheral shallows ranging in graded increments from 0.25 m to approximately 0.5 m in depth as well as two semicircular pulpits approximately 1.0 m deep. Unlike the wild, these pools do not have graded slopes leading from one depth to another, therefore, gradations of preferences cannot be measured. In three of the four pools ( Main, East holding and West holding), dolphins receive equal amounts of training time and feeding. The fourth pool (Medical), is used for medical procedures and for quarantine of new or sick animals. Some training and feeding is also done in this area.

The Main Pool is a very large pool open to the public viewing and stands on the south side of the facility. The top of its south wall is 1.80 m high clear acrylic for public viewing. Two thirds of the way towards the bottom are five large 2.0 m X 1.8 m viewing windows for lower level public viewing. In addition, there are two 0.6 m x 0.8 m underwater viewing ports on the maintenance side of this pool. The Main pool contains one wide shallower area, a beaching platform on the public viewing side of the pool and a dry feeding platform on the opposing side. Feeding and training sessions occur primarily in the areas however, other areas are used as well. The Main Pool also contains two shallow “pulpit” areas on the east and west ends of the pool and two narrow shallow shelves near the gates leading to the East and West pools, respectively. The East and West polls are all alike in all dimensions. They are both visible to the public but contain no viewing glass. Each pool however, has two viewing ports of like dimensions on the maintenance side. Each one has a narrow shallow shelf running almost completely around the other edges of the pool. The East Pool is closest to the staff and fish preparation centre. The two pools connect to the Main Pool via two independent sets of gates and connect to each other through the Medical Holding Pool. The Medical Holding Pool is the smallest of all four pools. It is located between the East and West Pools, connected through two independent sets of gates. It, like the rest, contains a shallow shelf area.

Out of all 84 instantaneous samples collect over a 18 day period. The data is analysed by different theoretical models based on pool or area dimensions : depth, surface area, volume (gallons) and simple location using chi-square goodness-of-fit test. Statistically, depth is the more conservative measure, but all other comparisons were made alongside. Depth, surface area, and volume are correlated for these pools. The dolphins showed unequal use of the three depths when compared to equal preference usage. This indicates that the deep, moderate, and shallow depth preferences differed from one another significantly. The dolphins were found most often (67.8% of the time) in the moderate depth areas of 5.49 m and least often(2.9% of the time) in the deep areas of 8.23 m, with the presence in the shallow areas falling in between these two at 29.7%. Another element that was considered were volume, that the dolphins were choosing pools based on the overall amount of water in each area. The assumption was made that dolphins would be equally distributed across the total volume so that larger areas i.e the Main Pool, through having more volume consequently, will be used more. The results found however, did not support this model. The dolphins were not using the different pools as would be predicted by proportional volume. Instead, the dolphins tended to use moderately sized pools most, then smaller areas, and the largest pool least. Similar circulations were made for surface area. Again, the assumption was made that dolphins will be equally distributed across the total surface area so that larger areas would be expected to have more use. Expected frequencies were calculated by dividing total surface area into individual surface areas and then multiplying by the total number of observations. This model was also not supported. Instead, the dolphins tend to use moderately sized pools most, then smaller areas, and the largest pool least. The final assumption made was that dolphins has specific area of pool preferences that were not related to any dimensional function. That is, the dolphins were biased towards specific areas due to factors such as history, ambient light, noise difference, or territorial and social factors. This model, yet again, was not supported. The dolphins did not choose areas of pools equally often but instead again chose moderate or shallow areas more often than large. There however, is some bias towards the West Pool areas, but the East Pool and the Medical Pool was used much more than the Main Pool.

All in all, even though it is evident that dolphins most often chosen areas that were moderately sized pools, then smaller pools and the deeper pools least, the dolphins were not acting in accordance with these predicted null hypotheses. The dolphins did not choose pools in proportion to any of these dimensions i.e larger pool dimensions paralleling greater use, nor did the dolphins behave in a way that indicated no preferences between depths and locations. Instead, the dolphins had preferences. These preferences were not correlated with increasing sizes or proportions but on the dimension of overall depth. It is impossible to state why the dolphins in this study preferred the West Pool over others, years of associational learning with the various areas and other factors, along with the influence produced by pool dimensions, may have combined to influence choice. What this study was able to conclude however, was that the dolphins absolutely seen little time in the Main Pool. These preliminary data support the suggestion that for this species, the Tursiops truncatus, bigger is not necessarily better.

-

Metal Gates ( Fig. 1 - 2 )

-

Keeps other animals out of Tiger Territory.

-

-

Double-Layer automatic fence ( Fig. 3 - 6 )

-

Allows keepers and staff to monitor the amount of cars entering the territory.

-

Slows cars down.

-

The distance between the two gates allow time for all customers to close their windows.

-

-

Holding facility ( Fig. 7 - 8 )

-

The built high enough so that the animals are able to stand on their hind legs at full height, allowing them to stretch and prevent developing any joint problems.

-

The built in concrete allows for a container for water, allowing the tigers clean water access as well as provide as enrichments simulation natural behaviour.

-

Apart from all of the furnishings , the placement of them is also key to ensuring maximum ease for both animals and keepers. For example, the distance of the individual structures from one another must be sufficient enough for the keepers’ cars to fit through to allow the keepers to monitor and/or distribute enrichment without getting in the way of customers whilst on duty.

Furnishings within the Enclosure.

Soft Furnishings ( Soft-Technology )

-

Logs + Trees ( See Fig 1 - 3 )

-

Allow tigers to climb, claw and mark their territory.

-

Tigers claw at trees as a way of sharpening their claws as the friction of the claw against the tree aids the outer layer of the claw to come loose, leaving behind a sharp new claw.

-

They also use trees to mark their territory as secretion from the glands in their paws leave deposits, easily picked up by other big cats.

-